Rigidity and Affordances in Systems

On how strategic points of rigidity in architecture can maximise adaptability

We tend to treat rigidity as the enemy of good engineering. But some of the most impactful architectural decisions I've made were about closing doors, not opening them. One example of this is Amazon's API mandate, a constraint that can create more freedom overall.

API as Rigidity

Mandating that all service-to-service communication must go through a standard interface is putting a significant constraint on the overall systems. Suddenly, teams can't just go pull from a source of truth directly. Need a specific dataset? It's not currently represented in the service's API? Time to go ask the team if they can create a new API path for you.

This depends a lot on the underlying implementation. GraphQL is going to be more flexible than a REST API with rigid response payloads and paths. With GraphQL, you can just ask the fields that you need, and adding a new field in the API is a matter of adding a new resolver.

But this nonetheless introduces some level of rigidity into the system: a forcing function that gets in the way of getting stuff done in the fastest and shortest way possible.

Type Systems as Rigidity

No one knowing me or looking at the older articles on this blog would be surprised to learn that I love Rust's type system. I wrote three different articles on using the type system to embed safety.

Once again, this is an example of rigidity. Rust's compiler enforces rigid rules, and learning to deal with the borrow checker is notoriously hard at first. However, this enables fearless concurrency, as most concurrency bugs are eliminated by the strict borrow and mutability rules.

On the type system, we also have explicit optionality and algebraic sum types1 that enable a high level of strictness in type representation, by creating once again more rigidity.

When Rigidity is Useful

I was working with a database that had a Recovery Point Objective (RPO) of zero seconds. We were storing representations of cloud-based resources. Losing data meant losing track of those resources. At best, they'd become zombies that'd increase our cloud bills without benefiting customers. At worst, they'd trigger alerts if something would try to recreate those resources.

Whenever we would introduce a bug that would write invalid data, we would have to manually connect to the production database and perform risky operations. We'd always have two engineers on a call, run steps in a transaction, double-check, to ensure we wouldn't cause more damage than necessary.

Junior engineers felt less confident making those types of changes, senior engineers would have to spend more time carefully checking pull requests to ensure they wouldn't cause problems. We can't rely on human behaviours alone — they don't scale, and they're fallible.

Instead, I proposed creating a write-safe domain model: a representation of our resources that wouldn't allow database corruption by design. You can no longer have a resource that exists without an ID, or an ID for a resource that doesn't exist. Rust's compiler wouldn't allow it.

It took about a month of engineering efforts. I started by showing how this would change the developer experience, built a proof of concept, then slowly migrated the entire codebase to this new pattern. This ended up eliminating an entire class of bug, improving the on-call experience2, reducing the stress on junior engineers, and making the PR review lighter.

We introduced a new point of rigidity, but we gained comfort, ease of mind, and the ability to write new features quicker, removing worries about potential bugs.

Affordances in Engineering

What we gained are affordances.

I've been going back-and-forth on whether I should call them affordances or flexibility. Flexibility is more understandable, but the concept of affordances is interesting and a bit more precise.

The term was coined in 1966 by psychologist James Gibson, and refers to the possibilities that the environment offers to the individual. Contrary to just flexibility, it embodies the relationship between the two, and the perception of the individual on the environment.

Creating a write-safe domain model didn't make engineers more comfortable because it gave them more choice. Instead, it gave them the impression that they could make changes more aggressively, knowing that the model would catch their mistakes at compile-time. This is all about the perception of safety.

APIs and Affordances

Going back to Amazon's API mandate, what affordances did teams gain?

During my time at Amazon, I noticed that teams owned their systems end-to-end. They were the sole gatekeepers. Because no other team could interact with their databases or internal systems, they could make fearless changes to how they worked. If you own all the consumers to your database, you know you can change the schema without breaking other consumers.

You get the same kind of fearless ability to make changes when you codify your contracts with your consumers. Comprehensive contract testing gives you test cases to make sure you won't break the specific use-cases for your public3 interfaces.

Thanks to GraphQL's strong typing and field-based queries, you can even go one layer deeper there. Apollo GraphQL has operations checks, which will compare proposed changes with recent queries against your API. While in REST you're never sure if you can safely remove a field, and therefore should always treat it as a breaking change, GraphQL here allows you to fearlessly remove it if no consumer uses it.

Accidental Rigidity

We discussed how introducing strategic rigidity in a system creates new affordances. But isn't it better to just leave the maximum number of doors open? After all, with no rigidity, everything is possible!

While I believe we shouldn't introduce rigidity too early in the lifecycle of a project or an organisation, there is a moment (and scale) when it can start biting back. As an organisation scales, as people join and leave, it gets harder and harder to know all the micro-decisions that were made over time, and why we made them.

This is where the doubt starts to creep in.

"Is anyone using this field? Will I break something by making this change? Let me check logs, traces, usage patterns before I make this change."

These concerns are all technically solvable, and in many cases won't lead to new outages or problems, but they slow down the process. Instead of fearlessly making changes, the number of affordances shrunk. There is a perception of risk now.

The larger an organisation, and the longer we wait to create that strategic rigidity the more affordances we lose. Systems get more and more tangled, because it's the shortest way.

Building Kowloon

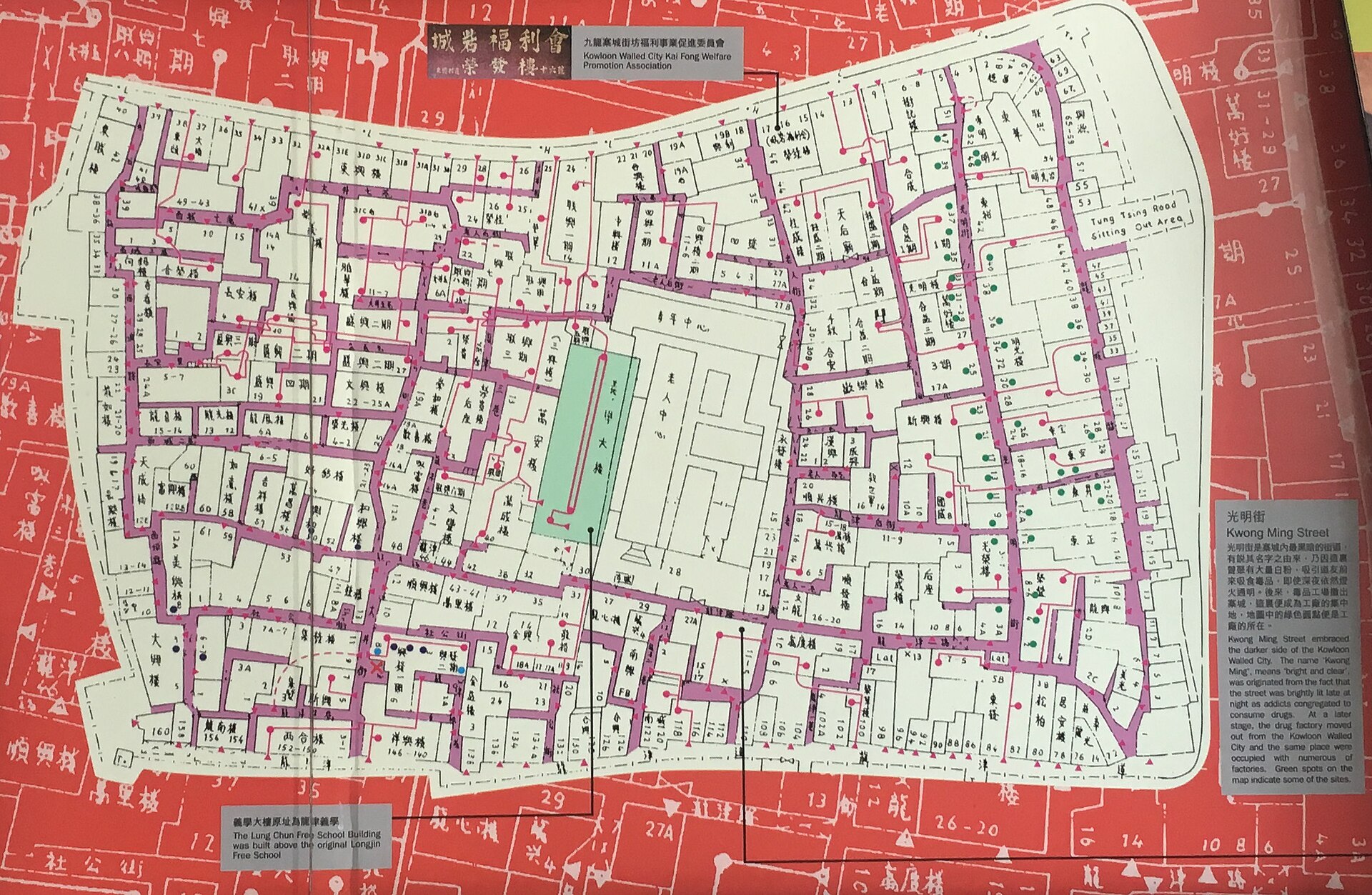

I often think about Kowloon Walled City when thinking about that accidental rigidity. It was the densest place on Earth, with 33 000 inhabitants, and a density of over 1 million per square kilometre.

It started as an odd piece of Chinese land stuck in Hong Kong, with no zoning laws, building codes, planning. People built what they needed, using the shortest way. Add a new apartment on top of what exists, create a new corridor, pass pipes and wires through other people's apartments.

Each decision made sense from a local point of view. But over time, nothing could be changed without risk. The walled city had become rigid, and structurally unsound.

Building a Planned City

The opposite problem exists. Planning too much, too early can reduce affordances as much as introducing that rigidity too late. Martin Fowler observed that most successful microservice stories started as monoliths that got broken up into separate components.

Microservices are a continuation of the API mandate. It's about creating strong, rigid boundaries to maximise inner affordances. But by doing it too early, we're creating rigidity when we don't know what the final structure should look like.

Principles for Rigidity

Over time, I uncovered four principles that guide my decisions on when and where to introduce rigidity in a system.

Uncertainty

The first one is uncertainty: the less you know about the problem space, the more flexible you should keep your system. This is where building microservices first fails. In the early stages of building, we're still discovering what the users want, how things will work end-to-end. Creating API interfaces too early makes the system too rigid to change. What if we don't need that service? What if the API design is wrong? Now we have to migrate.

I've seen this with organisations jumping to Amazon DynamoDB too early. This is a very powerful database, that can offer low latency and scale to virtually infinite sizes. The big caveat is that you need to understand your access patterns to leverage it to the fullest. On the other side, a good old Postgres database gives you more flexibility in the query patterns at the cost of scale. It makes it perfect for that early exploration, and then you can decide if you want a highly scalable database once you understand the domain better.

Layering

The second one is about on which layer we create rigidity. Complex systems are layered: they're built on top of multiple layers of technological decisions. Your distributed application might run on top of Kubernetes, running on a cloud vendor, using Linux, HTTP, TCP/IP, ethernet, and a whole other list of standards and layers.

Going back to real-world architecture, this fits into the model of shearing layers. Different parts of a house will change at different rates. The ground under a house tends to be pretty stable. We might change the facade, add a new room, remove a wall from a house. We might change the purpose of a room more often than we'll change those walls. We can move furniture around quite easily.

We went from a point of high rigidity at the lower layers, to a high number of affordances the higher we went. The shearing aspect in the model is that disrupting one of the lower layer will impact the higher ones. Breaking a wall changes the purpose and furniture arrangement of a room.

System architectures have the same kind of layering structure. Nowadays, almost all distributed systems will use TCP/IP, HTTP, Linux, etc. More and more companies are using Kubernetes as the base orchestration layer for their applications. These standards are rigidity that give affordances at higher levels. If different teams start using different operating systems, communication standards, etc. we are increasing the integration cost, which lowers affordances.

Scale

As we scale systems and organisations, we will always divide it into components that we can reason about. Without creating points of rigidity at scale, we now face an integration problem where many components need to communicate with many others. This creates many dependencies, points of complexity, etc. that increase the cognitive load for maintainers.

We cannot understand the full web of dependencies, interactions, etc. of a sufficiently large system. At that point, our understanding is limited, and we start being more cautious.

This is where we need to create standardised abstractions, new points of rigidity that help us make sense of the overall system.

That said, because complex systems are made of smaller components, we should maintain that flexibility when operating at a scale we can reason about. Small components of a larger system should conserve their inner flexibility, but use stronger interfaces.

While an organisation might not need strong API contracts at first, the API mandate becomes a useful tool at a certain scale.

Rate of Change

Finally, we have to consider the rate of change of the environment in which we operate.

Our points of rigidity are inflexible. We might face new technologies, competitive pressure, or a changing landscape that force us to rethink those points.

Let's imagine that we suddenly have a new API technology and customers are raving about it, pushing us to implement it as fast as possible. If we cannot just put a layer on top of our existing APIs, those points of rigidity are now a liability. They're preventing us from reacting to the environment.

AI is an interesting disruption in that space. Suddenly, many things we took for granted for years might no longer hold true. We're actively rethinking how we're building software, how people might interact with our systems, etc. The winners might be those that could react to that change quickly, who have enough affordances on these interfaces.

This is a pattern I've seen over and over. We want to maximise affordances: maximise our freedom and ability to react.

The best way to do this is by strategically placing points of rigidity, creating strong interfaces, leveraging standards on foundational pieces to maximise adaptability between those interfaces.

The harder question (which I'm still forming opinions about) is when to introduce these points of rigidity in systems. We often realise this too late, when systems are already deeply tangled.

As an aside: Sum types aren't the same as tagged unions. You can have untagged sum types. But this is just me ranting on semantics of type theory.

This mindset had an interesting side effect. Because we kept pushing for systemic fixes, we ended up having so few incidents that we had problems training new people for the on-call rotation. I'll need to write about this at a later date.

Here I'm using public as outside of your team or domain, but they might still be internal to your organisation.